Hens produce fewer eggs as they age and at times the eggs may not be marketable. The producer can temporarily reverse this decline or recover production for six or eight months by using an induced molt. By the time hens are two years old, and veterans of two or three production cycles, they will have to be replaced. The productive life of as many as 130 million hens must be terminated each year in the United States. On a per-farm basis, the figure may run from 50,000 to 125,000 hens; or it could potentially run to about three million hens in a large complex. The average weight of a spent hen today is approximately 3.5 pounds.

In former times, these surplus or spent hens were marketed to poultry processing plants for a few cents a pound. After all, such hens can be canned or cooked. If cooked and deboned, the broth can be used for soups; the meat, for salads, soups, and chicken pot pies. Now, however, the increasing size and concentration of the egg industry, changes in breeding patterns (to make both egg and meat production more efficient), and the increased availability of broiler breeder hens and broilers have reduced the market for spent hens.

Leghorn hens now have smaller bodies and less muscle tissue, and their bones are often brittle. Broiler breeder hens, on the other hand, are bred to grow rapidly and produce a large amount of meat, and they have minimal bone particle problems. Consequently, food processors find it less economical to buy the spent Leghorns, preferring the more tender broiler breeder hens with their higher meat tissue-to-bone ratio.

Difficulties in Rendering

Because fewer local processors want spent Leghorn hens, alternative markets or other management strategies must be used. Properly processed spent hen carcasses can be a valuable ingredient in animal feed mixtures for ruminants, poultry, mink farms, aquaculture, and pets. Getting the birds to renderers for eventual use in the feed milling industry is an attractive option but several obstacles remain to be worked out. For example, egg production units are far more scattered than broiler units. The rendering industry, on the other hand, is geographically distant from most egg producers. Only three plants in the United States are equipped to take the whole bird — feathers and all.

In addition, lengthy transportation to the renderers is costly and involves at least a degree of biological (biosecurity) risk. The replacement of spent hens is seasonal and the processed yield per bird is small. It is difficult to convince renderers who may be thinking about a commitment to this product source, that the supply of spent hens will justify their investment in facilities and product development. Egg producers faced with this new problem have resisted binding contracts. Many egg producers like to sell to traditional processors whenever they can while depending on renderers only when conditions compel them to do so. This situation is detrimental to establishing a rendering support structure for the layer industry.

Finally, renderers expect the birds to be delivered ready for processing — that is, dead on arrival. Therefore, even if rendering is the most attractive disposal option, all things considered, the egg producer is still the one responsible for the humane death of the spent fowl and the preservation of the carcass. If spent hens are to be disposed of on the farm, they must still be removed from the house and humanely killed. Then we must consider mortality management and whether the birds should be incinerated, composted, rendered, frozen, or fermented.

Humane On-farm Euthanasia

Depopulating an entire layer house will be emotionally and physically taxing. Like all management practices, where and how it will take place must be properly planned. Criteria include concern for the animals’ welfare, biological security, the environment, and the ability to perform the task efficiently and cost-effectively. The physical and emotional effects on farm personnel should also be considered. Guidance, standards, and regulations are available through local or state veterinary health and agriculture agencies. The American Veterinary Medical Association has specified cervical dislocation as one way that spent hens may be humanely killed. However, recent studies in Britain indicate that this method may not induce immediate unconsciousness.

The method used in many commercial poultry processing plants may also be adapted for on-farm use. In this procedure, an electrical stunner is used in combination with a compact shackling line. An arm of the line near the end acts as a tipoff, automatically dropping the birds into a truck for removal from the farm. Alternatively, the birds could be delivered to a second on-farm station for scalding and de-feathering the carcasses. Some drawbacks apply to this method, however. Care must be taken to ensure that each bird is properly stunned. Workers must be protected from dust and pathogens, depending on where the equipment is located; and the market for the spent hens must be strong enough to justify the investment in equipment, facilities, and training.

A third method of euthanizing the hens, developed at the University of Georgia, is to modify or dilute their air supply with carbon dioxide (CO2). This gas displaces air in a container and the birds die for the lack of oxygen. Carbon dioxide also anesthetizes the birds, making them less sensitive to pain. In on-farm trials of this technique, the induction of CO2 rendered the chickens unconscious within 30 seconds and death followed within two minutes. The gas was effective at levels of 45 percent or more.

Using a Modified Atmospheric Killing (MAK) Unit

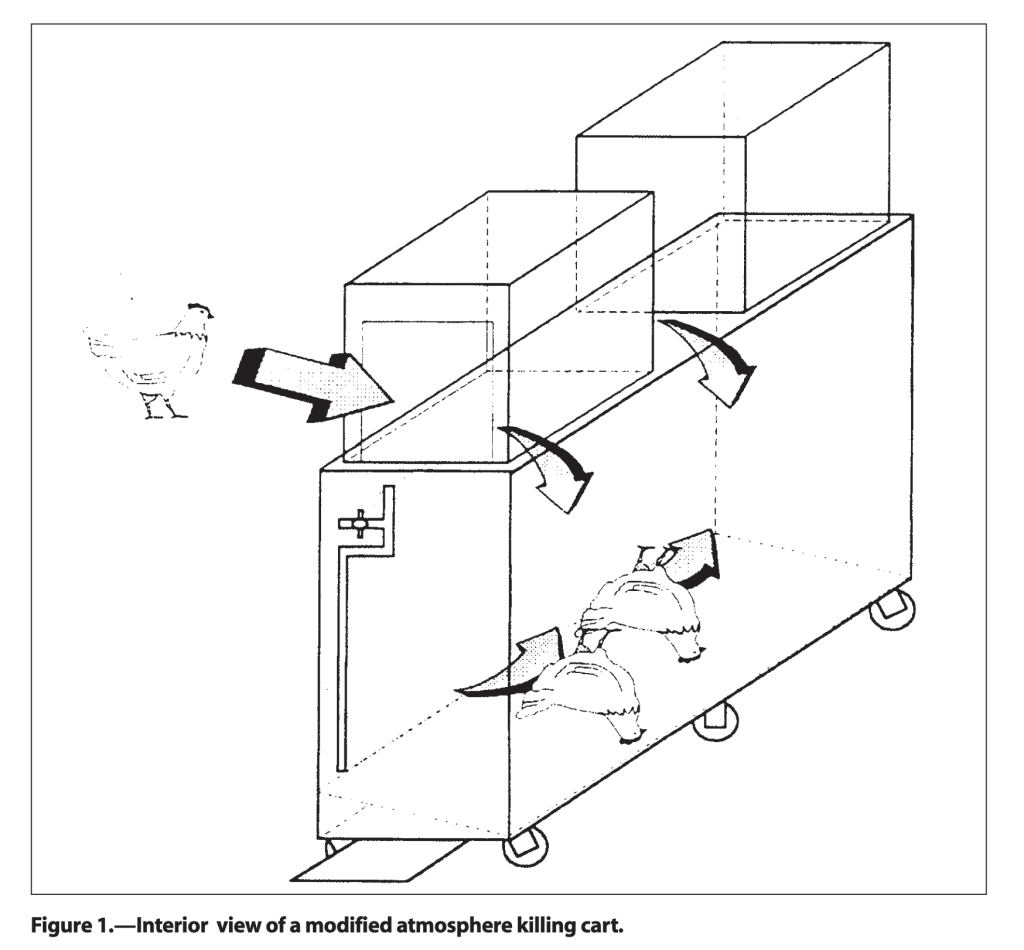

Producers can gain several advantages by using modified atmosphere killing to dispose of spent hens (Figure 1).

- The hen’s death is guaranteed without undue suffering;

- The method is technologically simple, requiring minimal training;

- The equipment, a supply of CO2 and a container, is easy to operate; and

- CO2 is relatively inexpensive.

The unit must be carefully monitored to ensure that the ratio of CO2 to air is sufficient to anesthetize the birds and shut down respiration, thereby avoiding smothering the birds.

Reduced labor costs and ease of operation are important, but the premium that producers put on being able to quickly, efficiently, and humanely euthanize these hens is reflected in all management options.

References

American Veterinary Medical Association. 1993. Report of the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 202:229-249.

Rich, J. 1994. Alternative Markets, Scheduling, Transport, and Handling of Spent Hens. National Poultry Waste Management Symposium. Athens, GA.

Ruszler, P. L. 1994. Utilizing Spent Hen and Normal Flock Mortality. National Poultry Waste Management Symposium. Athens, GA.

Webster, A.B. 2003. Personal communication. Department of Poultry Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Webster, A. B., and D. L. Fletcher. 1996. Humane On-Farm Killing of Spent Hens. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 5:191-200.