Incineration, or cremation, is a safe method of carcass disposal and may be the method of choice in areas plagued by poor site drainage and rocky soils. The major advantage of incineration is its ability to curtail disease. It is biologically secure, and it does not create water pollution problems. Even its by-product — ashes — is minimal, easy to dispose of, and unlikely to attract rodents or pests.

On the other hand, incinerators can be costly to install and operate and are expected to become more expensive as fuel costs rise. Further, while incineration destroys pathogens and poses no risk to water, its effect on air quality must be carefully monitored by poultry growers who choose this method of mortality management.

Incineration is not a casual or inexpensive undertaking. Barrels or other homemade vessels are unsatisfactory burners and have serious consequences for the grower if they result in air pollution or unpleasant odors. Using incineration to manage poultry mortalities must be carefully planned: it must comply with dead animal regulations, meet all air quality standards, and justify investments in commercial equipment and the risk of increasing energy costs.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, incineration is biologically the safest method of mortality management and simultaneously the method most likely to protect water resources. Producers considering this method of mortality management should consult with their state’s agricultural, environmental, and veterinary medical agencies on the best way to incorporate this method. Agricultural incinerators do not generally require a permit, though states vary on their requirements; they are designed to handle Type 4 wastes (e.g., animal remains, carcasses, organs, and solid tissue from farms and animal labs), but not other wastes (e.g., plastics and other organics).

Good Incinerator Design

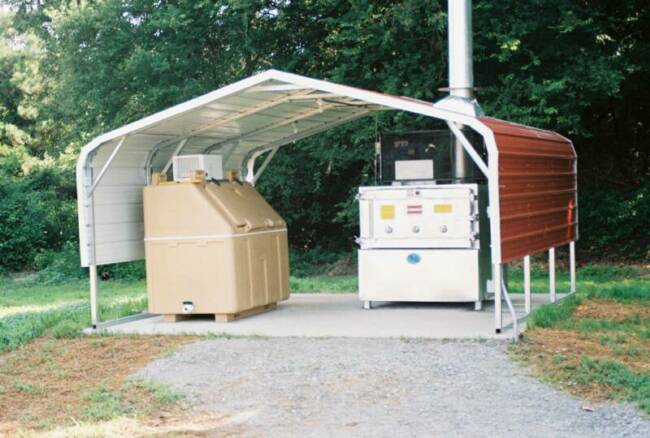

A variety of commercial incinerators are available, and each one should be installed according to the manufacturer’s specifications and local codes — typically outside, but under a roofed structure and away from any combustibles.

Incinerators should be sturdily built and able to accommodate daily mortalities. Indeed, they should be sized to handle large loads and high temperatures; however, very large-scale loads, for example, loads running over 100 pounds per hour may require an operating permit. Growers should carefully estimate the capacity needed to manage daily mortalities and include other disposal methods in their resource management plans to cover situations in which heavy, unexpected losses can occur.

An incinerator’s material qualities are unlikely to become a problem if the unit is bought from a reputable dealer since stainless, aluminized, or heat-tempered steel is commonly used in their construction. Insulated models and those with heat shields may save energy and minimize the unit’s exterior temperature. Those that have automatic controls will be more convenient and perhaps more economical.

Location and Operation

Incinerators should be used daily, so putting them in an area convenient to the poultry house will contribute to better management. Sheltering the incinerator from inclement weather will extend the life of the unit. For best results, it can be placed on a concrete slab.

To avoid nuisance complaints, locate the unit downwind of the poultry buildings, on-farm housing , and neighbors’ residences. Finally, always check that the discharge stack is far enough away from trees or wooden structures to avoid potential fires since incinerators burn at intensely high temperatures and discharge high temperature exhaust.

Incinerator Costs

Cost is no doubt the chief factor limiting the use of incineration in mortality management. The total investment includes the initial purchase, subsequent maintenance, and the interplay between the rate of burn and the price of fuel. Equipment costs vary depending on the size and type of the incinerator. Expendable parts and grates will need to be replaced periodically — perhaps every two or three years — and the whole system may need replacement (or overhaul) every five to seven years.

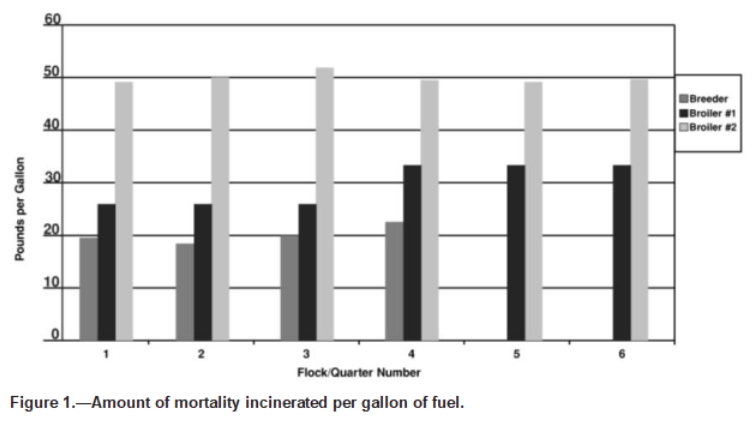

A study by Auburn University researchers over a one-year demonstration project (reported in 2002) used three commercial incinerators and two types of fuel — propane, and diesel — to compare the costs of incinerating three flocks of birds: one broiler breeder and two broiler flocks. Study results:

- The broiler breeder farm had an average mortality weight of 5.82 pounds over the four-quarter test and averaged 19.83 pounds of mortality per gallon of fuel (propane @ 85 cents/gallon) — an average of 4.26 cents per pound.

- Broiler No. 1 had an average mortality weight of 2.08 pounds of mortality per gallon (diesel @ 98 cents/gallon) — an average of 3.59 cents per pound.

- Broiler No. 2 had an average mortality weight of 0.93 pounds and averaged 49.89 pounds of mortality per gallon (diesel @ 98 cents/gallon)—an average of 1.99 cents per pound.

The study concluded that several factors contribute significantly to the cost and efficiency of incineration:

- Cull management within the first week of grow out.

- Actual cost of disposal tended to decrease with increased flock age: older birds accumulate more body fat that contributes to the combustion process.

- An incinerator with a thermocouple temperature controller that cycles the burner on and off may help reduce costs.

Growers have, for the most part, been unwilling to risk the high costs involved in this process, since they have no control over the price of fuel, and because the choice of incineration also means the loss of any nutrient value that the mortalities might have had if composted for land applications or rendered for other uses.

New technology may be the key to changing attitudes about incineration. Influenced by technological advances, current manufacturing specifications are producing a generation of incinerators that last longer, control emissions better, and burn more efficiently than older models in the field. Simply put: the new performance standards make it possible to separate the cost of incineration from the rising price of fuels. Thus, for example, trials on newer models have accomplished the same daily burn for less money than for older incinerators, even though fuel rates used in the computations were higher than those actually charged in 1990.

Incineration is an acceptable and safe method of poultry mortality management. It does not risk the spread of disease or water pollution. As technology succeeds in controlling its cost and its air emissions, incineration will become more competitive among the various methods available for managing this aspect of production. Growers considering incineration as a method of poultry mortality management are encouraged to plan this action in connection with their entire resource management system.

References

Blake, J.P., E.H. Simpson, J.O. Donald, and R.A. Norton, 2002. Economic Evaluation of Incineration as a Method for Dead Bird Disposal. In Proceedings of 2002 National Poultry Waste Management Symposium, Birmingham, AL. ISBN 0-9267682-6-8. National Poultry Waste Management Symposium Committee.

Brown, W.R., 1993. Composting Poultry Manure. Presentation. Poultry Waste Management and Water Quality Workshop. Southeastern Poultry and Egg Association, Atlanta, GA.

Donald, J.O. and J.P. Blake, 1990. Installation and Use of Incinerators. DPT Circular 11/90-014. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn University, Auburn, AL.