Paul H. Patterson, Professor, Emeritus of Poultry Science, Penn State University, php1@psu.edu, (814) 865-3414

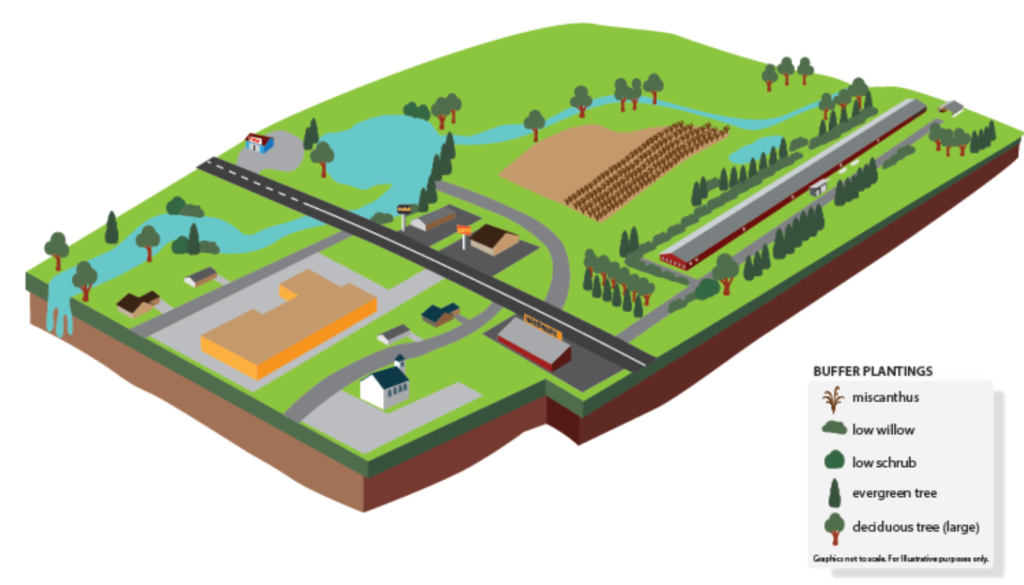

Vegetative buffer for poultry come in many types and sizes but are utilized predominantly for environmental conservation practices: 1. To landscape and beatify the farm and buildings and screen their view from the road and neighbors, 2. As vegetative filters for air quality (dust, ammonia, odor, endotoxins, microorganisms, etc.), 3. Riparian buffers to slow water run-off and trap and treat nutrients and sediment for water quality, 4. Energy conservation as a wind break, shade bank or snow fence, 5. Biomass buffers to produce bedding or fuel, 6. Shelterbelts for cover and protection of outdoor access birds, and 7. Silvopasture as part of a multi-cropping system with trees and poultry (Figure 1).For most of these conservation practices there are local, state and federal grants and cost-share programs to help support the installation and maintenance of vegetative buffers. Furthermore, they are not expensive installations and many pay dividends to the farm and for bird performance.

Figure 1.

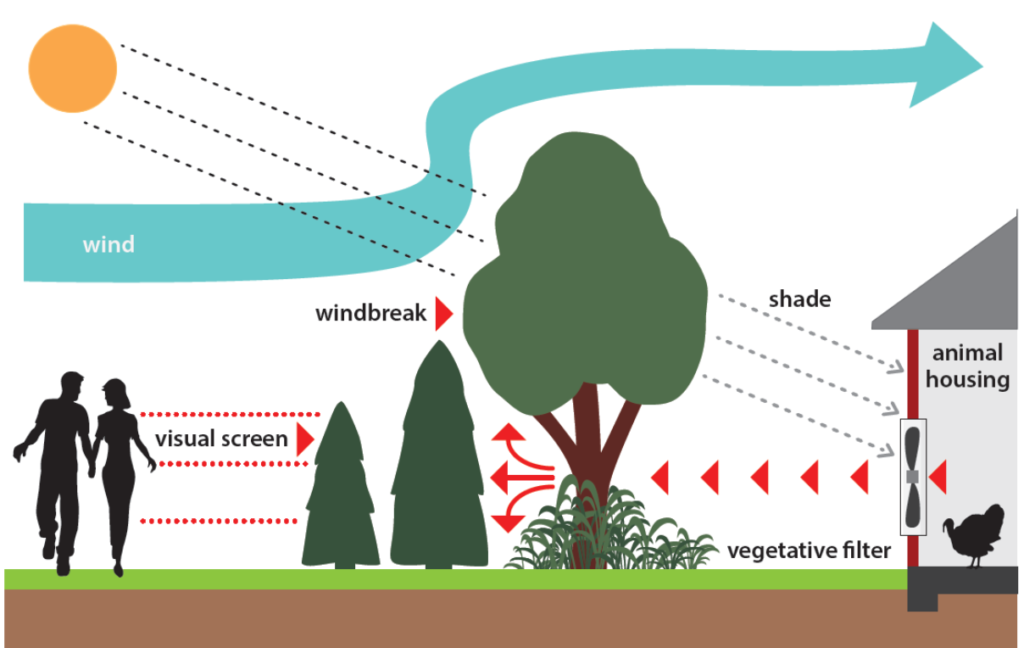

Urban encroachment on poultry farms is a real issue nationwide and may affect the future sustainability of the farm in the neighborhood if relationships are not good (Figure 2). Therefore, landscaping and screening the farm and activities can be helpful to soften the view of the barns and impart a more pleasing appearance. Often the act of planting trees and shrubs are viewed favorably and appease neighbors when tensions are high.

The Clean Air Act (1970), CERCLA (1980) or Superfund and EPCRA (1986) have historically been one means to scrutinize the emissions of poultry CAFO’s. In the wake of new emissions factors (AP-42’s) coming for poultry from the US-EPA in 2022, best management practices to mitigate both ammonia and particulate matter (PM) emissions will be helpful to navigate whole farm emissions. Vegetative filters are one conservation practice that can help reduce poultry dust, odor and ammonia emissions. Plant species vary in their ability to tolerate poultry house dust and ammonia and their ability to capture these emissions. Generally, warm season grasses, shrubs and deciduous trees tolerate dust better than evergreens like Arborvitae and others. Vegetation type and architecture also affects their ability to trap dust e.g. simple vs. compound leaves, smooth vs. hairy and sticky leaves and leaves vs. evergreen needles. Similarly, warm season grasses, legumes, shrubs and deciduous trees tolerate ammonia better than evergreens, especially pine species. Leguminous shrubs and trees that fix nitrogen are especially tolerant of ammonia emissions. Strategically designed, vegetative filters can trap and treat poultry house dust and ammonia reducing down-wind emissions and the odor that travels with dust.

Poultry farms have many impervious surfaces (roofs, roads, parking lots, concrete pads etc.) that accelerate water speed and the potential for erosion. Riparian buffers planted at the edge of these surfaces slows water speed and traps and treats nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus etc.) and sediment leaving the farm. These water loving plants including willows, dogwood, sycamore and others can tolerate damp soils and standing water in swales and ditches.

Conservation of energy and fuel savings can be realized using vegetative wind breaks to block the wind that can rob building heat and drive fan motors backwards. Snow fences strategically planted can direct snow away from barn roofs, prevent drifting and roof collapse. Furthermore, they can drop snow away from load-out doors, feed bins, entrances and parking to reduce the labor and fuel associated with snow removal. Shade banks are mini forests with multiple species that create a cool air environment that can typically be 10 degrees F lower than the barn yard temperature. They can shade the afternoon sun and are a source of cooler inlet air for bird comfort.

Biomass buffers can be renewable sources of warm season grasses like switch grass or Miscanthus giganteus that can yield (annually 3-8 or 5-11 tons per acre, respectively), or biomass willows, harvested every 2 to 3 years (25 to 35 tons, with 45% moisture). Both can be chopped and spread as a poultry bedding (best if 1-1.5 in) or utilized in a biomass burner as a fuel for hot air or boiler hot water heat distribution. Others have utilized the buffers as both a bedding and the spent litter as a brooding fuel to offset the amount and cost of traditional fuels like propane. Biomass buffers can frequently grow on marginal lands adjacent to poultry barns and require little fertilization and can scrub the soil of built-up phosphorus from repeated litter applications. They can also advance the farm toward carbon-neutral goals.

For outdoor access and organic birds, buffers can be planted to provide shelter for birds in inclement weather (wind, solar load, driving rain and snow) and provide cover from ground and aerial predators. Birds are often less inclined to go outdoors if the paddock or field is open with no cover, shade or protection.

Silvopasture is the practice of integrating trees, forage plants and domesticated animals together in an integrated, intensively managed system. Typically, these are dual cropping systems with plantation style trees and cattle grazing the understory. However, with poultry they can be similar tree/forage combinations or include fruit or nut trees, or a seasonal succession of mushrooms, greens, grasses, berries and nut crops to help feed and sustain the poultry. These systems can be nice niche markets for local poultry meat or eggs, however, one should not count on the silvopasture system providing any more than a fraction of the nutritional requirements of the bird.

In summary, for the conservation practices above, consider alternative plant species for different applications, soil analysis, site preparation, and the importance of buffer maintenance (weed & pest control, irrigation etc.) to ensure proper establishment. Finally financial support, cost share programs and resources for information and plant materials are available from the USDA and your states land-grant university.

Figure 2.