Introduction

The U.S. poultry industry is the world’s largest producer and second largest exporter of poultry meat. U.S. consumption of poultry meat (broilers, other chicken, and turkey) is considerably higher than beef or pork. Considering overall animal production in the U.S., the total number of chickens per farm has increased considerably. This national trend of producing more chickens on fewer farms is especially evident in the Mid-Atlantic.

From 1982 to 2002, while the number of broiler chicken farms decreased by 11 percent, the number of birds produced increased by 54 percent in Delaware, Maryland and Virginia (National Agricultural Statistical Service). While poultryproducers are increasing the efficiency of their operations, Mid-Atlantic States have been losing farmland, in most cases to development. From 1997 to 2002, Maryland, Delaware and Virginia, on average, have lost 5 percent of their state’s farmland. This loss of farmland totals almost 300,000 acres (National Agriculture Statistics Service). This trend of farmland loss is at a rate almost four times that of the nation as a whole. The encroachment of houses on farmland in the Mid-Atlantic, combined with the trend toward more concentrated poultry operations, points to a much greater need for vegetative buffers.

Benefits of Windbreaks/Buffers

Handling of Odor and Dust Particles

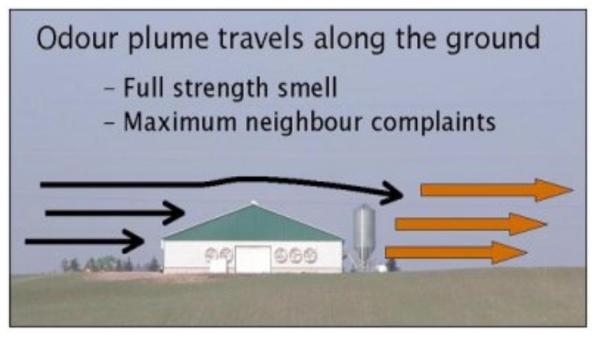

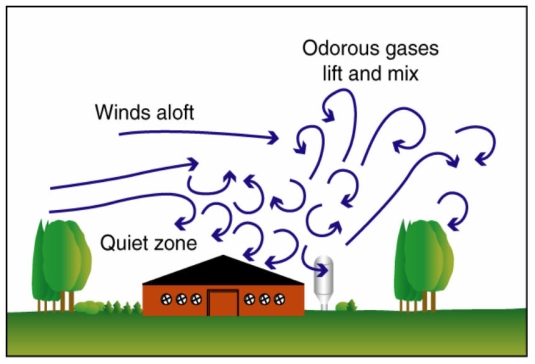

Tree and shrub buffers absorb gaseous ammonia, precipitate out dust by slowing the air speed from exhaust fans, and deflect the odor plume into the atmosphere above the buffer, all in a very cost-effective way. With odor management, the buffer becomes part of the overall management

A windbreak will significantly improve the visual appearance of the farm and foster good neighbor relations. Photo by George Malone.United States Department of AgricultureNatural Conservation Resources 2of the farm operation. Odor from poultry houses typically travels downwind, along the ground, in a concentrated plume. By planting trees and shrubs around poultry houses farmers can disrupt the plume and mix it with the prevailing winds to dilute odor.

Ammonia is the gas of greatest concern to the poultry industry. Plants have the ability to absorb aerial ammonia (Yin et al., 1998). This translates into higher growth rates, as plants located in front of exhaust fans were found to have higher amounts of nitrogen and dry matter weights compared to control plants (Patterson 2005). Plant growth is increased with the right amount of ammonia; however, there is a critical threshold where too much ammonia will cause tissue necrosis, reduced growth, and greater frost sensitivity (Van deer Eerden et al 1998). During the summer, trees reduced air velocity by 99%, dust by 49% and ammonia by 46% downwind of the trees (Malone 2006). The direction of the wind strongly influenced these results; wind blowing toward the fans “increased” the efficacy of the buffer while wind blowing in the opposite direction “decreased” this efficacy (Malone 2006).