Introduction to Vegetative Buffers as Biomass:

Vegetative buffers are gaining popularity in the Northeastern U.S. for their ability to serve multiple functions. Their value is increasing as they are being explored to enhance environmental stewardship on poultry farms. In addition to their merit as living filters for air and water quality, buffers can be harvested and transformed into bedding materials for poultry houses. This option would influence the decision as to which buffer species should be planted on a particular farm. In Pennsylvania, a variety of species have been successfully tested and implemented to function both as buffers and bedding material. These species include hybrid poplar, miscanthus grass, and biomass willow. Research is now being conducted to determine the efficacy of switchgrass as a bedding material, with the thought that it will perform similar to miscanthus, which was a successful bedding material in both pen and field trials. Although the species described in this article have been grown and utilized in Pennsylvania, there are other species that would likely produce similar results in both Pennsylvania and other regions of the country.

What species are recommended for biomass production?

The species commonly used for vegetative buffers are planted according to what the producer is looking to gain from this living filter or wall. All of the species listed below can be planted in the vegetative buffers as well as on their own in a field setting. However, the grasses and willow are most successful, where, after establishment, the biomass can be removed annually or biannually. More information on establishing these plants can be found on the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) website. The following are summarizations of the most common buffer species used for bedding as well as their harvesting and processing techniques.

Miscanthus Grass:

Miscanthus can be harvested annually after an establishment period of approximately 3 years. Harvesting takes place from the time when the plants’ nutrients recede into the root zone for the winter and the stems of the grass have dried down to before the new shoots emerge in the Spring. Optimal harvesting time is from November to March. Standard forage harvesting equipment is utilized to mow the grass and rake it into rows. At this point, it can be baled and stored or harvested with a forage harvester before bring placed wither into storage or directly into a poultry bam, as seen in figure 1.The later in the season the grass is harvested, the dryer it will be, with moisture levels from the field commonly found to be less than 20%. Leaving the grass standing in the field can be a way to hold the grass without storage if it will be utilized over the winter.

Switchgrass:

A species native to Pennsylvania, switchgrass is grown, harvested, and stored in a similar manner to that of miscanthus. It does not grow as tall as miscanthus, and the stems are narrower, leading to less biomass production.

Hybrid Poplar:

Trees are harvested when their minimum diameter is 10 inches. Certain cultivars grown in optimal conditions can reach this size in as little as 7 years. Trees from a buffer can be harvested alternatively and replanted each year to ensure that the functionality of the buffer remains intact while providing a continuous supply of bedding. If brought to a planning mill, the green logs can be shaved into a bedding material. This option may be best for those who have facilities close by so as to keep transportation costs low.

Biomass Willow:

Once established, these special species produce a large amount of dense biomass in a short period of time. The woody shoots can be harvested either annually or biannually. A modified forage harvester is typically used, and the best time to harvest is after leaf drop in the fall and before the shoots leaf out in the spring. The chips can be stored under cover until needed for bedding material.

Performance:

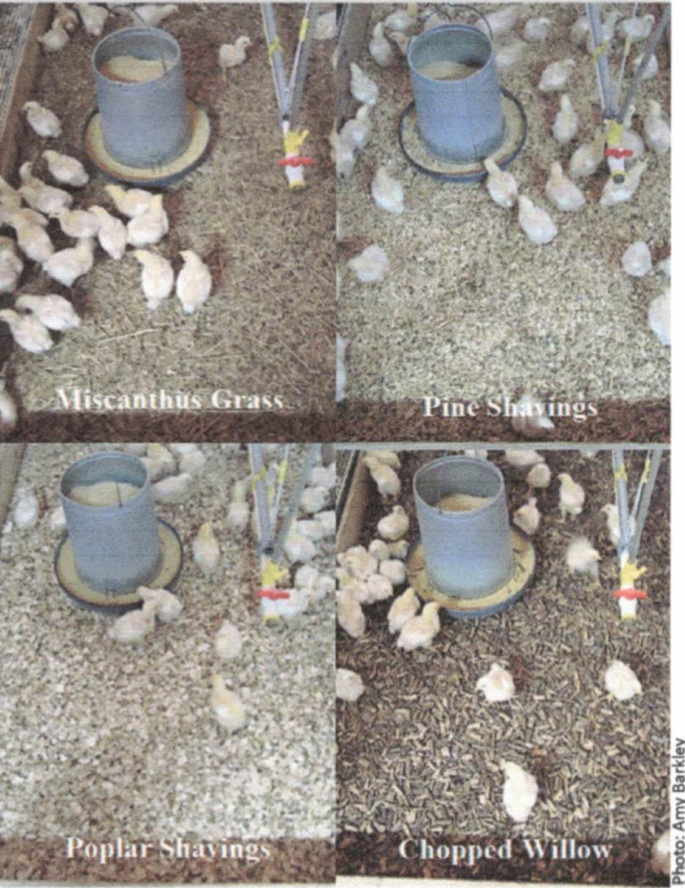

Generally, the beddings produced from vegetative buffer species perform as well as traditional softwood shavings. In a recent replicate pen study involving chopped miscanthus grass, shaved poplar logs, and chopped willow, it was found that there were slight differences between these bedding materials in terms of bedding quality and broiler performance. Overall, it was concluded that any of these alternative beddings would be appropriate to use. However, it should be noted that willow chips should be small enough as to not hinder young birds. Miscanthus grass has also been utilized in commercial poultry operations in Pennsylvania. The same conclusions about its quality and performance in addition to bird performance have been made.

Use in Biomass Burners:

For producers that rear birds on single-cycle litter systems, this litter has fuel value to brood chicks when burned in a litter burner or gasifier. Depending on the plant species, biomass bedding materials placed in a house at the same depth as softwood shavings may result in spent litter that is higher in carbon than traditional softwood shavings, generating more heat per ton than traditional litter. Recent research has indicated that spent litter from willow and poplar bedded birds had higher BTUs per ton than litter comprising of softwood shavings or miscanthus grass. Litter from miscanthus bedded birds was found to have equal or more energy than softwood shavings over the course of multiple trials. The BTU content of each spent litter type is additionally dependent on the characteristics of the biomass particles, the initial depth of the bedding material, and the moisture content of the spent litter.