The basic complaint associated with confined animal feeding operations is odor. Even though odor is generally more irritating than dangerous, it often evokes outrage from neighbors. Many growers who may previously have ranked odor among the least pressing of their problems are now encouraged to make it a priority. Odor, like flies, is ubiquitous and unlikely to be totally eliminated. But it can be controlled. Wherever strong odor is a problem, the most recent tendency is to treat it as a pollutant and quite possibly to find the grower in noncompliance with regulations.

Odor may be endemic to feed lots, houses, litter storage facilities, lagoons, and land applications, but its strength, or nuisance quotient, depends on site-specific conditions and management procedures, such as location, sanitation practices, season, climate, time of day, and wind direction and speed. Having an appropriate poultry waste management system is essential, and the most useful odor prevention measures are therefore found throughout the fact sheets included in this handbook.

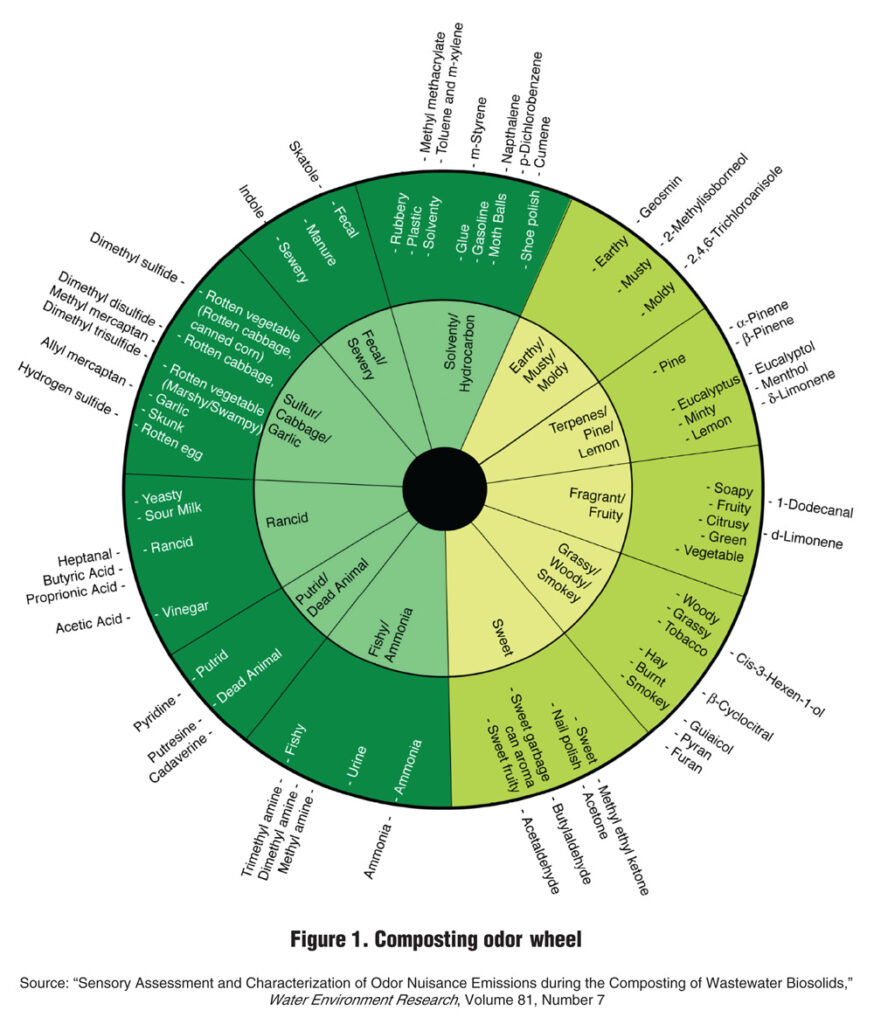

Litter is a naturally occurring biodegradable waste. Ammonia and other nitrogen compounds and some gases generated in the decomposition process are the primary sources of the offending odor. If the decomposition process occurs in the presence of sufficient oxygen, few odors are produced. However, anaerobic decomposition produces many odorous and some dangerous gases. At least 75 odorous compounds can be produced in the decomposition process, including, for example, volatile organic acids, aldehydes, ketones, amines, sulfides, thiols, indoles, and phenols. For this reason, it is good management to store litter in a covered, dry stack facility, and to follow spreading by a incorporating the litter into the soil. Properly applied litter increases plant growth and contributes to natural nutrient recycling (see Dry Manure Management) with no environmental damage and little odor.

How Odor Affects Us

The physiological sense of smell, which is perhaps never as keen as sight or hearing, can vary as much as a thousandfold from person to person, and can be affected by age. Thus, for example, children under age 5 seem to like all smells; children over 5 do not, though one’s sense of smell decreases with age. At age 20, people have 80 percent of their physiological sense of smell; at age 80, about 28 percent. Other things that make a difference in one’s sense of smell are smoking habits, allergies, and head colds. Behavioral responses to odor are equally diverse. Some individuals can be genuinely unaware of odors that are a nuisance to others. In addition, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide should be monitored since both suppress the sense of smell. Odor fatigue makes it impossible to smell certain odors, while simple adaptation also accustoms one to certain smells. However, studies to determine the effects of odor on people living near confinement facilities or on farms where litter is managed show that (1) factory receptors renew themselves every 30 days; (2) frequency and duration are weather related; and (3) odors can definitely affect people’s moods and nervous systems and cause depression and nausea.

Within these limits, it is possible for individuals to sense the presence or absence of an odor — even when they cannot quantify its five basic properties: intensity, degree of offensiveness, character, frequency, and duration. The more accustomed we are to odors the higher the threshold must be before we detect them.

Updating Standard Practices

As good management is the key to controlling odor, so keeping up with new developments is important for all managers. New developments are part technological breakthroughs and part trial and error; and many of them have been discovered by farmers solving real life problems. Consider, for example, the growers’ concern for the birds’ welfare and for controlling odor. Choices that the grower makes before and during production, for example, about which bedding material to use and what diet to feed the birds, may contain some of the trade-offs the grower is looking for.

Some growers report that they have achieved good results — better flock health and less odor — by using recycled paper, leaves, or other green manure as an alternative to straw bedding material. Others have found that the addition of phytase to birds’ diets helps them use less phosphorus; thus, they excrete less. And, as the long-term effect of this choice may well be that less phosphorus is available for land applications, the grower who uses phytase obtains a three-way trade: less nuisance odor, less environmental risk, and better bird performance.

Other management choices for laying operations that reduce odor, contribute to the flock’s performance, and protect the environment include flushing the houses’ water system with clean water, keeping the waterers in good condition, and drying the manure. The use of separation and set-back distances, riparian and other buffers and windbreaks, and restrictions on land applications on frozen ground or when rain is predicted — also help control odor and contribute to the growers’ bottom line and reputation for good citizenship.

Above all, growers should not try to cover up odors by putting their heads in the sand, blaming other farm sites, or thinking of their neighbors as city slickers unused to earthy smells. Nor should they rely on the other kind of cover up: the one that uses chemicals or other additives to mask the odor. Most of the claims for such commercial products are still unconfirmed.

Here, then, is the fundamental principle: Know the causes and cures. Unless growers know how odors are generated, that is, the factors producing them, they cannot know what control practices can be used to counter their effects. Once we have a grip on the causes, four basic strategies are available.

- Of most importance, prevent odor from developing in the first place. It bears repeating: locate the poultry facility away from other farm buildings and residences, handle litter in a dry state as much as possible, and remove all mortalities, broken eggs, and spilled feed immediately.

- Alter the unpleasant smells by chemical or microbiological treatment. That is, use a collection and storage treatment that can include drying the litter, composting, anaerobic digestion, and disinfection.

- Contain the odors: prevent their escape into the atmosphere by regular washdowns for layer operations to minimize dust and feathers, and by using well-maintained waterers, good ventilation equipment, and bedding materials that repel moisture.

- Disperse and dilute odors once they do escape into the atmosphere. For example, consider the wind direction and other weather conditions before applying litter, and plant or take advantage of natural windbreaks, riparian forests or buffers, and injection or other soil incorporation methods to reduce the odor associated with land applications. In addition, exhaust fans can be pointed away from other buildings or down to the ground so that stale malodorous air is deflected into the ground near the housing facility.

Methods used to capture and treat gas emissions are needed to protect air quality and to reduce odor. They include the use of covered storage pits or lagoons, soil adsorption beds and filter fields, and appropriately planned land applications. Odors associated with toxic gases are protective; noxious smells, on the other hand, are a nuisance and leave us feeling unprotected. The former trigger safety precautions; the latter evoke the strongest possible repugnance, and may increase rather than decrease now that scientists are coming up with ways to measure odor.

Adjudicating claims between noses is a risky business. However, growers are not alone in this effort. Assessments of on-farm conditions can be a helpful management tool and a powerful support in contested cases. Local, state, and federal natural resource agencies, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the Cooperative Extension Service can help growers assess their management systems, prepare appropriate resource management plans, and learn how to maintain simple but sufficient records to show that their operations are effectively managed to prevent both odor and environmental contamination.

Conclusion

The best way to deal with odor problems is at the beginning of the production cycle and through a commonsense approach. The problems have mundane origins: they may be related to improper or mismanaged burial pits, emissions from incinerators or land applications, and intensified by increasing urbanization, unanticipated adverse weather conditions, and specific, often seasonal, activities in the production cycle. Other fact sheets in this handbook deal with these practices.

Simultaneously, however, the chemical basis of odors, variations in detection thresholds, and differences in the degree of offensiveness make it imperative to handle the problem of odor via litter management and public relations. Attitudes must always be taken into account since odor is better accepted by individuals who see the grower as a friend, community member, and neighbor. Protecting natural resources and improving relationships may be the long-term solution to abiding in the same watershed.

References

Odor Monitoring and Detection Tools – Biocycle

Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, 1997. Integrated Animal Waste Management. http://www.netins.net/showcase/cast/watq_sum.htm.

University of Minnesota, 1997. Strategy for Addressing Live- stock Odor Issues. Feedlot and Manure Management Advisory Committee’s Livestock Odor Task Force Report and Recommendations. http://www.bae.umn.edu/extens/manure/lotfr.html.

Powers, W., 1994. Odor Abatement: Psychological Aspects of Odor Problems. National Poultry Waste Management Symposium, Athens, GA.

Sweeten, John, 1994. Odor Abatement: Progress and Concerns. National Poultry Waste Management Symposium, Athens, GA.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1992. Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook. AWMFH-1. Soil Conservation Service, Washington, DC.