Poultry raised for commercial purposes produce large amounts of manure which — unlike the manure of free range or pastured animals — is a collectible resource. It contains valuable plant nutrients and other chemicals that, if properly managed, can be returned to the land or processed for other uses. Therefore, anyone planning to undertake a confined animal feeding operation must give serious attention to the proper handling of manure and other waste products.

Factors influencing the choice of animal waste management systems begin with the type and size of the operation being contemplated, the grower’s management skills and inclinations, the local environment, federal and state laws and regulations, and the effect of the proposed waste management plan on the operation’s economic forecast. The importance of the choice increases in proportion to the volume and potential value of the residual materials.

A Voluntary Environmental Management Approach

The National Farm Assessment Program (Farm*A*Syst) expanded from a 1991 pilot project in Wisconsin and Minnesota. It is funded by the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

A single checklist provides a simple way to identify (1) where a grower’s management actions and environmental concerns intersect; (2) the degree to which current practices may be putting these vulnerable points at risk; and (3) strategic actions one can take to correct problems and reduce risk. The checklist, or self-assessment, is comprehensive but not lengthy; and it is completely private. Other Farm*A*Syst program materials explain practical management strategies and environmental regulations and how to find technical resources and financial help. Consult with local Cooperative State Research, Extension, and Education and NRCS offices for more information, access to the program, and technical support.

Concern for soil and water quality is the key to selecting a successful waste management plan, but criteria to be considered include the size of the operation, the economic consequences involved, and the growers’ (and company’s) personal management styles. The complexity of the system, whether it is dry or liquid, and the best management practices that can be used to minimize its effects on the environment are the subjects of subsequent fact sheets in this series.

Begin with the Land/Water Interface

Whether the wastes or by-products that accompany poultry growouts are good or bad for the environment depends in large part on interactions between the activities of the producers and the ecosystem. Hence, planning efforts begin with an assessment of the farmstead’s location in relation to rivers, lakes, ponds, ditches, and sinkholes; the chemical and physical properties of the soil profile; the availability of agricultural land in the production area; and the possible effects of poultry

production on the naturally occurring cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus.

Why Begin with Water?

Agricultural activities, including mishandled or excessive poultry wastes, are a major source of nonpoint source pollution. Crop production, pastures, rangeland, feedlots, and other animal holding areas are agricultural sources of pollution in the U.S. waters assessed; 50 to 60 percent of the water quality problems in rivers and lakes and 34 percent of polluted waters in more urbanized coastal areas are stem from agricultural sources. Bacteria, sedimentation, and nutrients are the leading pollutants.

Properly managing manure, controlling runoff, and planning nutrient management in conjunction with land applications will reduce or eliminate much of the proposed source of pollution and contribute to more productive farming. Most nonpoint source pollution problems can be controlled if growers know how nutrients and soil interact and plan accordingly. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium move through cycles on a farm. As nutrients, they go from crops to animals (in feed) to the soil (waste applications) and back again to other crops. If the cycle holds, everything works as it should. But too many nutrients already in the soil or too much waste applied to the land can move with the soil into surface water or through the soil into groundwater until their presence in the water reaches unacceptable levels, and thus impairs water quality.

Nitrogen

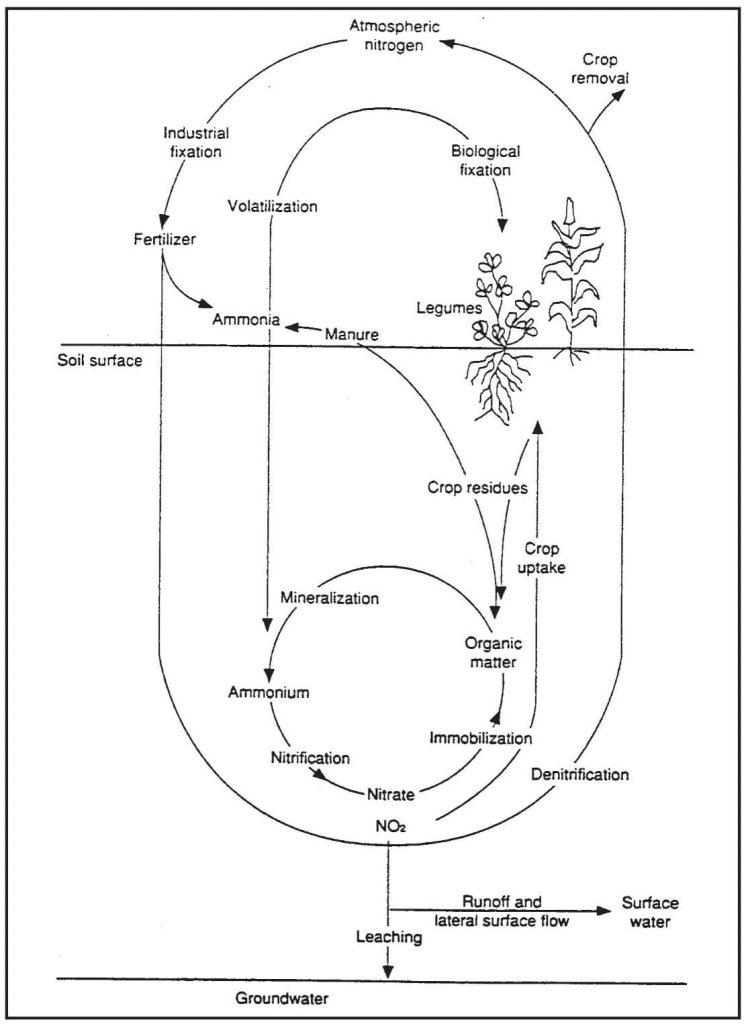

Of the three major nutrients in poultry waste, nitrogen is the most complex and hence the most likely to contribute to environmental problems. Most of earth’s nitrogen exists as nitrogen gas in the atmosphere (see Fig. 1). It can be transformed into inorganic forms by lightning or into organic forms by plants, such as soybeans, alfalfa, or clovers. Nitrogen can also be transformed into inorganic forms (commercial fertilizers) by energy intensive processes. Most of the nitrogen found in animal wastes is organic nitrogen. A smaller amount of the nitrogen in litter is ammonium. Organic nitrogen can be mineralized or converted by soil bacteria into inorganic nitrogen, the form in which nitrogen is available to plants. Excessive organic and ammonium forms of nitrogen will be transformed in soil into nitrate nitrogen (that is, into water soluble nitrogen).

Source: Pennsylvania State University, College of Agriculture. 1989. Groundwater and Agriculture in Pennsylvania. Circular 341. Reprinted with permission.

Volatilization, surface runoff, and leaching can cause losses of nitrogen from the cropping system regardless of source (e.g., manure, commercial fertilizer, or municipal biosolids). Surface runoff can move dissolved nitrogen (especially nitrate), ammonium nitrogen attached to eroding soil particles, and organic nitrogen contained in organic or plant residues into streams and lakes. Nitrates also move with the soil or leach through well-drained soils past the root zone into the groundwater supply. High levels of nitrate can be toxic to humans. Nitrates reduce the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen and may cause internal suffocation. Scientists tell us that too much nitrate can affect the weight, feed conversion, and performance of poultry. Too much nitrogen in surface water makes the water less productive and may result in fish kills.

Phosphorus

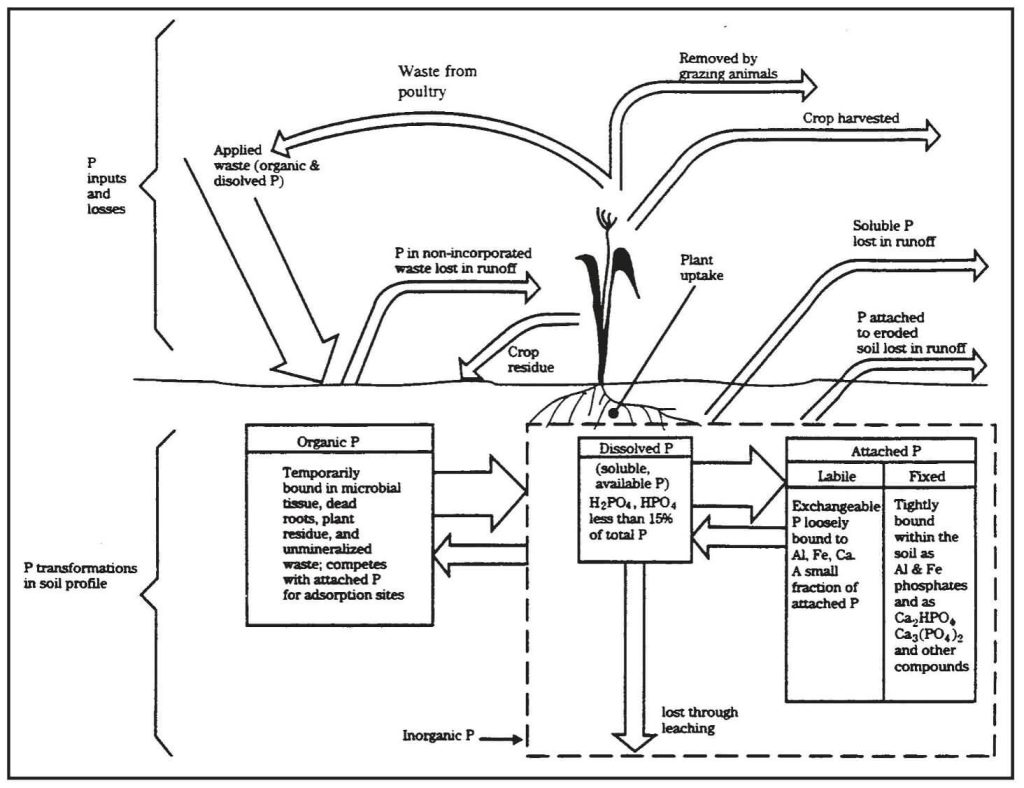

Poultry wastes also contain significant amounts of phosphorus (see Fig. 2). Phosphorus, like nitrogen, is essential for plant and animal growth and also contributes to environmental problems. In fact, it seems to cause the huge algae blooms that make lakes unfit for swimming and ultimately deplete their oxygen supply, deadening the water and killing fish. Phosphorus has become a major cause of poor water quality.

Phosphorus exists in either dissolved or solid form. Dissolved phosphorus usually exists as orthophosphates, inorganic polyphosphates, and organic phosphorus in the soil. Phosphorus in the solid form is referred to as particulate phosphorus and may be composed of many chemical forms, grouped in four classifications:

- adsorbed phosphorus, which attaches to soil particles;

- organic phosphorus, which is found in dead and living materials;

- precipitate phosphorus, which is mainly fertilizer that has reacted with calcium, aluminum, and iron in the soil; and

- mineral phosphorus, the phosphorus in various soil minerals.

Approximately two-thirds of the total phosphorus in soil is inorganic phosphorus; the remaining one-third is organic. Both forms are involved in transformations that release water-soluble phosphorus (which can be used by plants) from solid forms, and vice versa.

Phosphorus-laden soil or dissolved phosphorus can move via runoff into rivers, lakes, and streams, where it causes excessive plant and algae growth, which in turn depletes the dissolved oxygen content in the water. Phosphorus-enriched waters contribute to fish kills and the premature aging of the waterbody. In the end, the beauty and use of the waters are seriously curtailed. Even relatively small soil losses may result in significant nutrient depositions in the water.

Controlling soil erosion and proper land application of phosphorus-containing wastes will greatly reduce the amount of phosphorus in water. While not normally a great concern, care must also be taken to prevent soluble phosphorus from leaching into groundwater.

Applying poultry waste to land at rates based on supplying the nitrogen needs of grain or cereal crops can lead to a phosphorus buildup in the soil. Planting forage crops in rotation with grain crops will help remove excess phosphorus. Maintaining soil pH at the recommended level is also an effective and economical practice for maximizing phosphorus use. Crops use phosphorus most efficiently when the soil pH is between 6.0 and 7.0.

Soil phosphate levels are an important consideration in calculating poultry litter application rates. Land applications should be made only to soils that do not already contain excessive phosphate levels. Each waste source should be analyzed prior to land application to determine proper phosphorus application rates.

Potassium

Potassium in poultry waste is a soluble nutrient equivalent to fertilizer potassium. It is immediately available to plants when it is applied. Potassium is fairly mobile but does remain in the soil to help supply plant needs; for example, strong stems, resistance to disease, and the formation and transfer of starches, sugars, and oils. Excessive amounts of potassium can inhibit the growth of some plants at certain stages of development. Small amounts of potassium may be leached to groundwater, especially in sandy soils; however, potassium or potash is usually not a threat to water quality or considered a pollutant.

Metals and Trace Elements

Metals and trace elements, such as copper, selenium, nickel, lead, and zinc, are strongly adsorbed to clay soils or complexed (chelated) with soil organic matter, which reduces their potential for contaminating groundwater. However, excessive applications of organic waste containing high amounts of metals or trace elements can exceed the adsorptive capacity of the soil and increase the potential for groundwater contamination. Excessive application of some metals (for example, copper) can be toxic to plants whose growth is needed to take up other nutrients.

Surface water contamination is a potential hazard if poultry wastes are applied to areas subject to a high rate of runoff or erosion.

Salts

Dissolved salts, mainly sodium, in high concentrations interfere with plant growth and seed germination, and may limit the choice of plant species that can be successfully grown. Poultry waste with low salt content and a high carbon to nitrogen ratio can improve soil water intake, permeability, and structure.

Using Litter Nutrients Wisely

High nitrate levels in groundwater and high phosphorus levels in surface water may indicate that too much litter or fertilizer is being applied on too little land. Yet the fact that poultry litter is high in nutrients is precisely its value. The nutrients in this resource make it an excellent soil conditioner and fertilizer. Growers can maximize the benefits of having this resource and help protect their local water resources from high nutrient levels by planning and operating an effective nutrient management system.

Application practices will vary with the area’s cropping practices, topography, and other environmental and economic conditions. Waste and soil testing are the simplest and most important aspects of nutrient management. They help farmers monitor the nutrient supply to guarantee that it is adequately controlled to produce the best crop yields and maintain water quality. When properly recycled, nutrients are not wastes but opportunities to improve the overall farming operation.

References

Bandel, V.A. 1988. Soil Phosphorus: Managing It Effectively. Fact Sheet 513. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Maryland, College Park.

Carter, T.A. and R.E. Sneed. 1987. Drinking Water Quality for Poultry. PS&T Guide No. 42. Cooperative Extension Service, North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Fulhage, C.D. 1990. Reduce Environmental Problems with Proper Land Application of Animal Wastes. WQ201. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Missouri, Columbia.

Goan, H.C. and J. Jared. 1991. Poultry Manure — Proper Handling and Application to Protect Our Water Resources. PB 1421. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Keeney, D.R. and R.F. Follett. 1991. Overview and Introduction. Chapter 1. In Managing Nitrogen for Groundwater Quality and Farm Profitability. Proceedings. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI.

Killpack, S. and D. Buchholz. 1991. What Is Nitrogen? WQ251. University Extension, University of Missouri, Columbia.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1992. National Engineering Handbook 210, Part 651. In Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook. Soil Conservation Service, Washington, DC.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1995. The National Water Quality Inventory: 1994 Report to Congress. EPA841-R-95-005. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Wells, K.L., G.W. Thomas, J.L. Sims, and M.S. Smith. 1991. Managing Soil Nitrates for Agronomic Efficiency and Environmental Protection. AGR-147. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Wicker, D.L. 2002. Successful Nutrient Management Programs. Presented at the National Poultry Waste Management Symposium. Birmingham, AL.