Poultry litter is a valuable by-product of the poultry industry. It is, for example, a natural soil amendment — a source of nutrients and organic matter that can increase soil tilth and fertility. If it is mishandled, it is also a potential pollutant of surface and groundwater.

Developments within the poultry industry and increasing restrictions or regulations on the disposal of poultry waste have significantly altered the industry’s attitudes about this immense resource. Broiler operations alone produced over 21 billion pounds of litter each year, and because production is concentrated in very small geographic areas, waste management planning is extremely important.

Historically, poultry growers applied poultry waste to their farms as much to dispose of the material as to use it for fertilizer. Difficulties with this practice increase with the supply for several reasons:

- Less cropland is farmed than 20 years ago, and more poultry operations exist than in the past.

- Typically, more nutrients are brought onto the farm in the form of feed than leave the farm in the form of meat or eggs. The nutrients left on the farm are in the manure and bird mortalities.

- Other resources (wastewater, composted residential waste, and sludge) are also being used for land applications, which increases competition for the remaining croplands and pastures.

- We know now that valuable nutrients — nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium — are squandered and water resources are threatened if land applications of waste are overdone or misapplied.

- Regulations regarding waste management are now enforced by many states.

Increasingly, concern for water quality has become a major catalyst for the upsurge of interest in new approaches to land application. Today’s growers are finding that they can no longer afford to dismiss the benefits of poultry waste planning, which include increases in farm production, environmental protection, and lower costs.

Plan Components

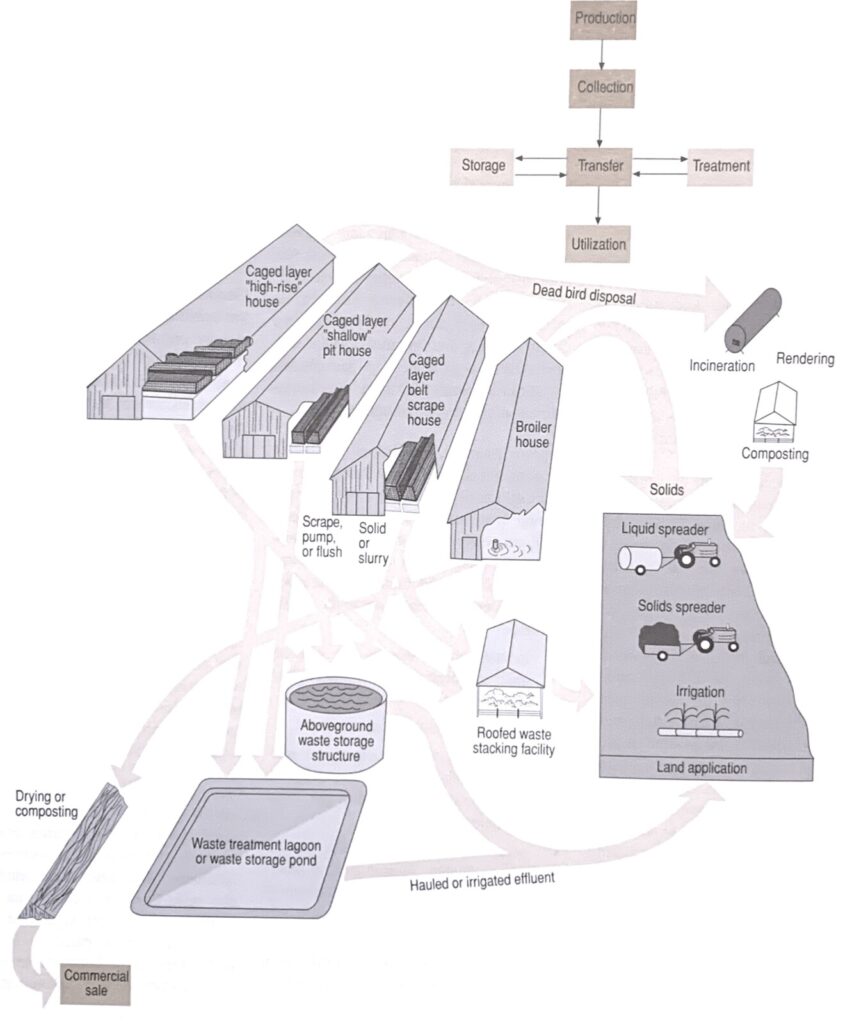

The waste management system must provide for the collection, storage, and final distribution (use) of manure and dead birds in an environmentally safe way. State laws generally do not permit direct discharges of animal waste into water, and many states require permits for confined animal operations beyond a certain size. Soil and water quality considerations are the key to choosing among types of waste management systems (for example, whether to install a dry or liquid system).

Components will depend on the operation’s size, operating plan, and the producer’s access to technical expertise. For example, one facility may have an incinerator for handling dead birds; another may have an incinerator and a composting facility.

Components of waste management systems include, but are not limited to, the following:

- composting facilities;

- debris basins;

- dikes, diversions, and fencing;

- filter strips and grassed waterways;

- transportation and other heavy-use area protections and equipment;

- irrigation schedules and equipment;

- nutrient management planning, including soil and manure testing procedures;

- pond sealings or linings;

- subsurface or surface drains, or both; and

- waste storage ponds, other storage structures, and treatment lagoons.

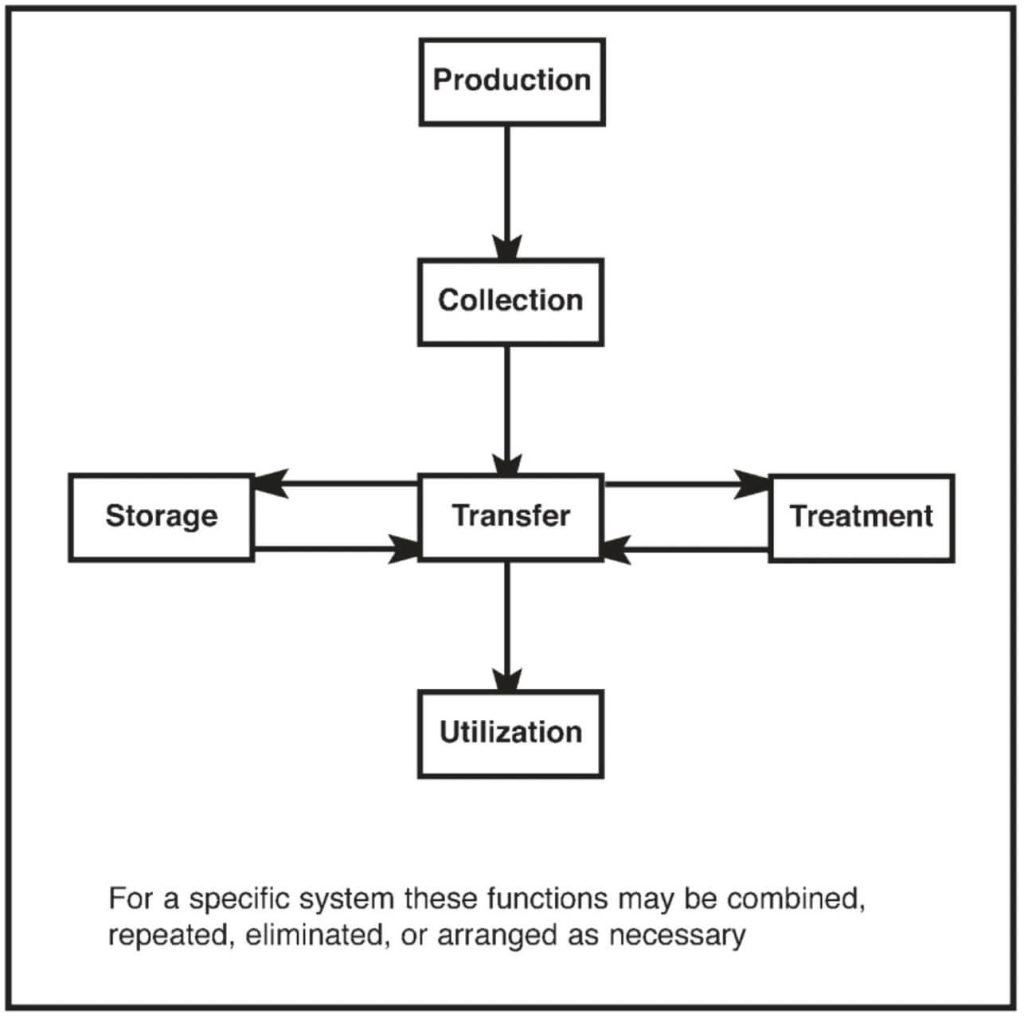

The relationship among these components is shown in Figure 1. Note that the drawing contains a broiler house and several examples of caged layer houses. Figure 2 shows the six stages of animal waste management.

Diagram above needs alt text (description) to summarize contents.

Diagram above needs alt text (description) to summarize contents.

An Integrated Approach

Traditionally, poultry growers have efficiently disposed of litter as soon as possible by spreading the manure or litter on croplands or pasture. Now growers must begin their waste management inside the poultry house. Along with the objectives of flock health, production, and odor control, today’s waste management planning must also protect water quality and contribute to a profitable farm operation. Integrating these broad objectives requires growers to develop other options in addition to land application.

Thus, to be profitable and to protect our natural resources — air, soil, water, plants, and animals — poultry growers must plan their waste management practices carefully. They must base application rates and timing on soil test results and crop removal needs along with an analysis or estimate of the nutrients contained in the manure or litter.

Poultry waste management planning begins before actual production and may have as many as six steps (Fig. 2). The first step is to understand the waste management process. What are these wastes? How much does a particular operation produce on an annual basis? Where or how can these wastes be used? The second step, once the quantity and quality of the wastes have been determined, is to put efficient collection methods in place.

The third and fourth steps are to have adequate storage facilities and the ability to transfer or move the waste from the point of collection to the appropriate point of use. In some cases, a fifth step is included to determine whether biological, physical, or chemical treatment of the wastes is needed to reduce the potential for pollution or to prepare the wastes for final use.

The sixth and final step in the waste management plan is to use the wastes — normally, for land application as a fertilizer and soil improvement or as a feed ingredient — in accordance with the nutrient management plan. Growers will usually have identified sufficient land on which to apply the waste before production begins. If enough land does not exist, other uses must be assigned or additional lands located for disposal.

The Benefits of Nutrient Management

Nutrient management actually begins when the poultry waste process has proceeded from collection and conservation to the actual use of these products for land applications or energy and feed production. Nutrient management planning matches the nutritional requirements of the soils, crops, or other living things with the nutrients available in the manure or litter, thereby preventing nutrient imbalances, health risks, and surface and groundwater contamination.

Nutrient value is based on the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content of poultry waste. This value can be enhanced by matching the nutrients available in the resource with the nutrients needed in the application. This planning also reduces disposal and handling costs. Nutrient management planning makes it possible to use poultry manure to replace commercial fertilizers or at least to reduce their use — thereby reducing some costs of crop production. Nutrient management also minimizes the potential harmful effects that overapplication can have on the environment.

An essential goal of nutrient management is to make sure that any poultry waste, especially manure or litter, is used safely and effectively. Nutrient management is, in fact, the key to using this waste as a beneficial by-product. To obtain maximum benefit and prevent possible contamination of surface and groundwater, the following management principles and practices can be applied:

- Develop and apply a Resource Management System, an Animal Waste Management System, a Nutrient Management Plan, or similar program. Assistance is available from the local offices of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Cooperative State Research, Extension, and Education Service, state departments of agriculture, or soil and water conservation districts.

- Find out if your state uses nitrogen as a basis for land application requirements. If not, is phosphorus a concern in your area?

- Analyze poultry waste regularly to monitor major nutrients and pH levels. Proper soil pH will help maximize crop yields, increase nutrient use, and promote decomposition of organic matter.

- Apply only as much fertilizer (nutrients) as the crop can use.

- Calibrate equipment and apply waste uniformly.

- Incorporate poultry waste into the soil if possible to reduce runoff, volatilization, and odor problems.

- Do not spread poultry waste on soils that are frozen or subject to flooding, erosion, or rapid runoff prior to crop use.

- Spread poultry waste during specific growing seasons or as scheduled for maximum plant uptake and to minimize runoff and leaching.

- Use proper storage methods prior to land application.

- Maintain a vegetative buffer zone between the field of application and adjacent streams, ponds, lakes, sinkholes, and wells.

- Follow approved conservation practices in all fields.

- Be considerate of neighbors and minimize conflicts when transporting or land applying poultry waste.

Training, technical assistance, and in some cases, financial aid are available to help growers and crop farmers identify problems and develop solutions for using poultry waste in their specific regions. The Natural Resources Conservation Service and Cooperative Extension Service have developed work sheets for animal waste management systems that help growers estimate production, obtain soil and manure analyses, and make economical and practical use of the organic resources generated on the farm. These agencies and others can help growers design facilities and develop overall resource management plans.

References

Bell, D. 1982. Marketing Poultry Manure. University of California, Cooperative Extension, Riverside.

Cabe Associates, Inc. 1991. Poultry Manure Storage and Process: Alternatives Evaluation. Final Report. Project 100-286. University of Delaware Research and Education Center, Georgetown.

Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. 1989. Poultry Manure Management: A Supplement to Delaware Guidelines. Cooperative Bulletin 24. Delaware Cooperative Extension. University of Delaware, Newark.

Donald, J.O. 1995. Broiler Waste Management Planning. Circular ANR-926. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn University, Auburn, AL.

Fulhage, C. 1992. Reduce Environmental Problems with Proper Land Application of Animal Wastes. WQ201. University Extension, University of Missouri, Columbia.

Margette, W.L. and R.A. Weismiller. 1991. Nutrient Management for Water Quality Protection. Bay Fact Sheet 3. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Maryland, College Park.

Missouri Department of Natural Resources. 1993. Obtaining a DNR Letter of Approval for a Livestock Waste Management System. WQ217. University Extension, University of Missouri, Columbia.

Swanson, M.H. No date. Some Reflections on Dried Poultry Waste. University of California Cooperative Extension, Riverside.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1991. Improving and Protecting Water Quality in Georgia . . . One Drop at a Time. Soil Conservation Service, Athens, GA.

———. 1991. Improving water quality by managing animal waste. WQ3 in Water Quality and Quantity for the 90s. Soil Conservation Service, Washington, DC.

———. 1992. National Engineering Handbook 210, Part 651, in Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook. Soil Conservation Service, Washington, DC.

———. 2003. Poultry Production and Value Summary, 2002. National Agricultural Statistics Service, Washington, DC.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1993. The Watershed Protection Approach: A Project Focus. Draft. Assessment and Watershed Protection Division. Washington, DC.

Wicker, D.L. 2002. Successful Nutrient Management Programs. Presented at the National Poultry Waste Management Symposium. Birmingham, AL.

Zublena, J. 1993. Land Applications: Nutrient Management Plan. Presentation. Poultry Waste Management and Water Quality Workshop. Southeastern Poultry and Egg Association, Atlanta, GA.