A well-planned co-product management system will account for all wastes associated with a poultry agricultural enterprise throughout the year, from the production of such wastes to their ultimate use. The more integrated the waste management system is with the grower’s other management needs, such as production, marketing, pest control, and conservation, the more profitable the farm will be.

The best method for managing poultry manure depends on the type of growing system, dry or liquid manure collection, and the way the house is operated. Misuse of poultry manure can reduce productivity, cause flies, odor, and aesthetic problems, and pollute surface and groundwater. Poultry manure can produce dust and release harmful gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, methane, and ammonia. Fresh manure is troublesome if it gets too wet.

Poultry wastes are handled differently depending on their consistency, which may be liquid, slurry, semisolid, or solid. The total solids concentration of manure depends on the climate, weather, amount of water consumed by the birds, type of birds produced, and their feed; it can be increased by adding litter or decreased by adding water.

Within the poultry industry, broiler, roaster, Cornish hen, pullets, turkey, and some layer operations are dry; live bird processing, some layer, and most duck and goose operations are liquid. In most dry operations, the birds are grown on floors covered with bedding materials. The manure collected from ducks, geese, and large high-rise layer operations is usually pure or raw manure, unmixed with litter though it may be mixed with water during clean out.

Kinds of Poultry Waste — Manure and Litter

Livestock manure is feces and urine; poultry manure mixed with a bedding material is called “litter”, and its constituent properties vary, depending on how the chickens are fed and their age and size (Fig. 2). The only way to know for certain its concentration and composition is from lab analysis. The amount of manure a given flock produces can be estimated from the amount of feed the birds eat. Roughly 20 percent of the feed consumed by poultry is converted to manure. Poultry raised in cages or raised floors produce a manure-only product (Fig. 3).

Other conditions that affect litter quality include the age and type of the bedding material, excessive moisture, frequency of clean outs, and subsequent storage conditions. The constituents of the litter can be estimated from prior analyses of similar wastes, but all litter should be analyzed at least once a year until its nutrient value is firmly established (after that, it may be tested less frequently, perhaps every two or three years unless management practices change).

The volume of litter varies widely, depending on the producer’s management style. Indeed, many of the same conditions that determine the litter makeup also affect its quantity. For example, the feed type, number of clean outs, climatic conditions, and bird genetics are all factors. Broilers, however, produce on average 2.25 pounds of litter per bird or about one ton per year per 1,000 birds: about 80 cubic feet of litter for each 1,000 birds.

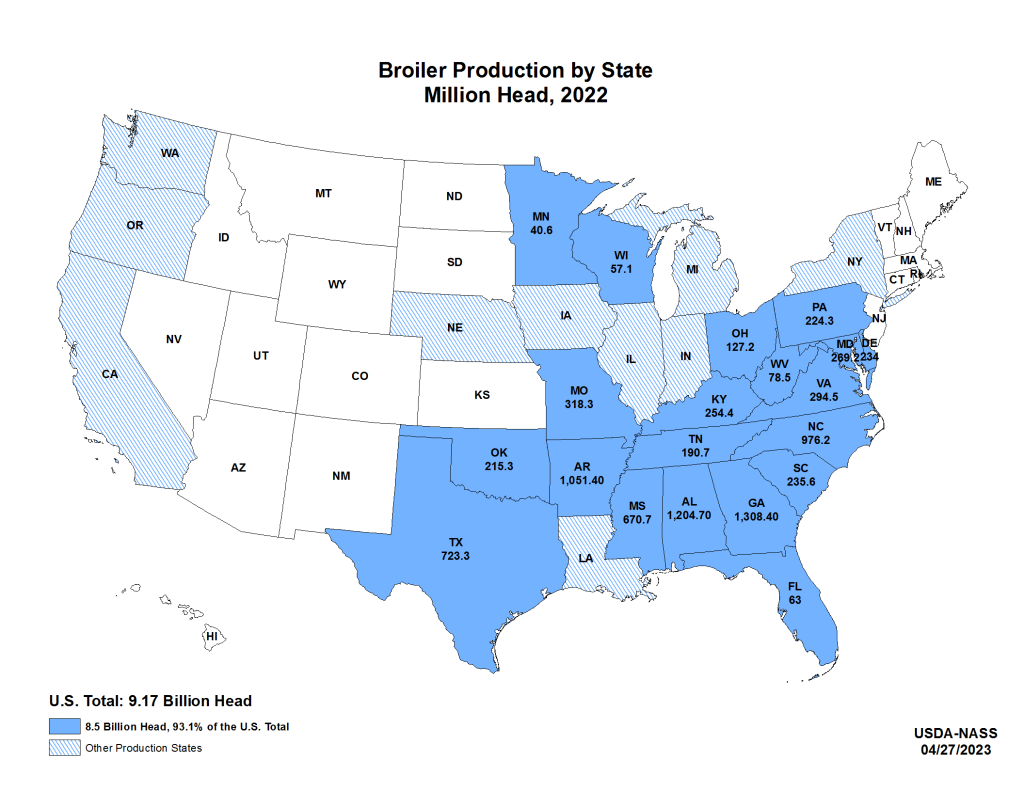

In 2022, nearly 20.6 billion pounds of litter were produced by broiler operations in the United States (2022 Broiler production = 9,170,000,000; NASS, April 2023). Litter Generated = avg. 2.25 lb./broiler/year.

That much litter can and must be responsibly used. Bedding materials, manure, and used feed have nutrient value for land applications, and are also useful as a fuel source, a feedstock ingredient, or as part of the recipe for composting. Table 1 estimates the amount of litter produced by 1,000 birds grown to different market weights and Table 2 lists the average amount of fertilizer nutrients in broiler litter. Other minerals in broiler litter include: calcium, magnesium, sulfur, sodium, iron, manganese, zinc, and copper.

Table 1. Litter produced per 1000 birds

| Birds by market weight | Estimated litter produced |

|---|---|

| 2 lb. bird | 0.45 ton per cycle |

| 4 lb. bird | 1.0 ton per cycle |

| 6 lb. bird | 1.5 ton per cycle |

Table 2. Average nutrient content of broiler litter

| Fertilizer nutrients | Average amount in broiler litter |

|---|---|

| Nitrogen | 58 lb. per ton |

| P2O5 | 50 lb. per ton |

| K2O | 60 lb. per ton |

Management Practices

Litter should be kept from becoming overly wet. In a well-managed house, the moisture level in litter will range from 25 to 35 percent. Higher moisture levels increase litter weight (forming litter “cake” or compressed, wet material) and reduce its nitrogen fertilizer value. However, litter cake must be removed from the house between clean outs to protect the remaining litter and reduce ammonia generation potential. After its removal, the cake should be stored to dry it and minimize odor; precautions should be taken to prevent groundwater contamination; and stormwater should be diverted from contact with the litter.

If cake is properly removed from the house, total clean outs can be delayed. Checking for water leaks in the house, ventilating properly, and keeping the house at an even temperature are management practices that reduce the production of cake. The total weight and volume of litter will depend on the type of bedding material used, its depth, whether cake is present or removed, and the length of time between clean outs. Its quality also depends on how it is removed from the house, whether the floor is raked or stirred between flocks, and how it is stored.

Open Range or Enclosed Housing

Fields, pastures, yards, or other outdoor areas have been used as ranges for chickens, turkeys, ducks, or game birds. Such areas must be located and fenced so that manure-laden runoff does not enter surface water, sinkholes, or wells. Unless these areas are actually feed lots (confinement areas that do not support vegetation), no collection and storage of manure is required. Instead, the manure is recycled directly to the land. Best management practices, such as pasturing the animals away from sinkholes and other water resources, and preventing animal access to streams, apply to these operations. In confinement operations, by contrast, the manure is collectible and can become a valuable co-product of the operation.

In enclosed settings, dry and liquid co-products require different collection, storage, handling, and management systems. The management of dry manure depends primarily on how it is stockpiled or stored from the time of its production (at clean out) until it is properly land applied. The following paragraphs describe general house conditions that affect the production and quality of this material and the principles of dry waste management. Liquid co-product management is explained in an additional fact sheet contained in this section.

Dry Waste Storage Facilities

Common procedures for managing dry broiler litter or dry manure from layer operations center on protecting this material after it is removed from the house until its valuable fertilizer nutrients can be put to other uses. Litter that is not properly stored suffers a reduction of nitrogen from releases to air and water. These losses represent both lost income and the potential for surface and groundwater contamination. To prevent such losses, facilities used for storing dry poultry waste should meet or exceed the following conditions:

- a sufficient capacity to hold the waste until it can be applied to land or transported off the farm

- adequate conditions of temperature and humidity to permit storage of the waste until it is needed

- a concrete or impermeable clay base to prevent leaching to groundwater

- appropriate roofing, flooring, and drainage to prevent rainfall, stormwater, runoff, and surface or groundwater from entering the waste

- a location that prevents runoff to surface waters or percolation to groundwater

- ventilation and containment for effective air quality and nuisance control

The ideal storage design is a roofed structure with an impermeable earthen or concrete floor. This design keeps the litter dry, uniform in quality, and easy to handle, and it also minimizes fly and odor problems. Management plans that allow for proper storage achieve the following:

- improve the production environment

- reduce the amount of ammonia released from litter

- reduce the volume of litter cake

- extend the time between clean outs

- increase the product’s value and flexibility

- protect the quality of adjoining waters

Kinds of Storage Facilities

Generally, storage facilities can be open, covered, or lined (permanently lined, in some cases); or they can be bunkers or open-sided buildings with roofs. Perhaps the most common facilities for collecting and storing poultry litter are dry-stack buildings, or covered outdoor storage facilities with impermeable earthen or concrete flooring.

Floor Storage

Most broiler, roaster, Cornish hen, pullet, turkey, and small layer operations raise birds on earthen or concrete floors covered with bedding material (Fig. 2). A layer of wood shavings, sawdust, chopped straw, peanut or rice hulls, or other suitable bedding material is used as a base before birds are housed. Litter cake is typically removed after each flock, though other litter management practices such as tillage and windrowing have been adopted. A complete clean-out can be done after each flock or once every 12 months or longer, depending on the producer’s requirements and management practices. Slat or wire floor housing, used mainly for breeder flocks, can be handled the same way. Floor storage is the most economical method to store litter. Care must be taken not to leave foreign material such as wire, string, light bulbs, plastic, or metallic items in the litter.

Dry Stack Storage

Temporary storage of litter in a roofed structure with a compacted earthen or concrete floor is an ideal management method (Fig. 4). Large quantities of co-products can be stored and kept dry for long periods of time. To prevent excessive heating or spontaneous combustion, stacks should not exceed 5 to 8 feet and large variations in moisture content should be avoided. Dry stacks promote ease of handling and uniformity of material and removal is relatively easy. Dry stacks protect the resource from bad weather and make it available for distribution or land application at appropriate times.

A variation on this option is a stack or windrow located in an open, well-drained area and protected from stormwater runoff. The stack must be covered with a well-secured tarpaulin or other synthetic sheeting.

Other Storage Methods

Storage in covered or uncovered facilities is not the only alternative. Field storage on the farm, applicator storage (that is, storage by the crop farmer who will use the litter or manure for fertilizer), cooperative storage (several growers sharing a larger facility off-site), and private storage (by entrepreneurs who will sell or process the litter to create new products) are additional methods of waste storage. Each method must be evaluated in terms of cost, environmental safety, industry practice, and regulatory parameters. State regulations vary on how co-products can be stored or staged in fields prior to distribution.

In some states, permits may be required for a storage facility or for other parts of the resource management system. Possible zoning restrictions may also influence the choice of storage systems allowed. Proper storage is essential to optimize manure fertilizer value for crops, provide ease of handling, and avoid groundwater or surface water contamination.

Open Range or Enclosed Housing

Fields, pastures, yards, or other outdoor areas have been used as ranges for chickens, turkeys, ducks, or game birds. Such areas must be located and fenced so that manure-laden runoff does not enter surface water, sinkholes, or wells. Unless these areas are actually feed lots (confinement areas that do not support vegetation), no collection and storage of manure is required. Instead, the manure is recycled directly to the land. Best management practices, such as pasturing the animals away from sinkholes and other water resources, and preventing animal access to streams, apply to these operations. In confinement operations, by contrast, the manure is collectible and can become a valuable co-product of the operation.

In enclosed settings, dry and liquid co-products require different collection, storage, handling, and management systems. The management of dry manure depends primarily on how it is stockpiled or stored from the time of its production (at clean out) until it is properly land applied. The following paragraphs describe general house conditions that affect the production and quality of this material and the principles of dry waste management. Liquid co-product management is explained in an additional fact sheet contained in this section.

Processing

Consider also the feasibility of processing alternatives. Poultry co-products can be:

- composted and pelletized to produce soil amendment and fertilizer products

- converted to feed for beef cattle or to briquettes for fuel

- deposited in lagoons for anaerobic digestion and methane production

Above all, use soil and manure testing to improve the success (crop yields) and timing of land applications. Practice biosecurity (that is, safeguard the application from disease-causing organisms and fly larvae) at all times.

Using poultry litter as a feed supplement for cattle has occurred for many years. Methods of handling and storage can greatly affect the quality of the material as a feed ingredient. Litter with the highest nutritional value is found in the upper layers of the litter pack where spilled feed contributes to the nutrient value. Large amounts of soil, if included in the litter harvested for a feedstock, increase the ash content and reduce the nutritive value of the litter. Feed litter should be deep-stacked at least three weeks to ensure that sufficient heat is generated to kill pathogens.

Remember: The use of manure storage structures is a best management practice for the protection of environmental quality, and an interim step in co-product management. It should be followed by nutrient management planning and appropriate use of the co-product for land application.

References

Brodie, H.L., L.E. Carr, and C.F. Miller, 1990. Structures for Broiler Litter Manure Storage. Fact Sheet 416. Cooperative Extension, University of Maryland, College Park.

Boles, J.C., K. VanDevender, J. Langston, and A. Rieck, 1993. Dry Poultry Manure Management. MP 358. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Arkansas, Little Rock.

Boles, J.C., G. Huitink, and K. VanDevender, 1993. Utilizing Dry Poultry Litter — An Overview. FSA 8000-5M-7-95R-S563. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Arkansas, Little Rock, AR.

Cabe Associates, Inc., 1991. Poultry Manure Storage and Process: Alternatives Evaluation. Final Report. Project Number 100-286. University of Delaware Research and Education Center, Georgetown.

Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control and Cooperative Extension Service, 1989. Poultry Manure Management: A Supplement to Delaware Guidelines. University of Delaware, Newark.

Donald, J., 1990. Litter Storage Facilities. DTP Circular 10/90 2004. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn University, Auburn, AL.

Donald, J.O., and J.P. Blake, F. Wood, K. Tucker, and D. Harkins, 1996. Broiler Litter Storage. Circular ANR-839. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn and Alabama A&M Universities, Auburn, AL.

Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission, 1994. Planning Considerations for Animal Waste Systems for Protecting Water Quality in Georgia. In cooperation with USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Athens, GA.

Payne, V.W.E. and J.O. Donald, 1991. Poultry — Waste Management and Environmental Protection Manual. Circular ANR-580. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn, AL.

Ritz, C. and W. Merka, 2016. Maximizing Poultry Manure Use through Nutrient Management Planning. University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Science Extension publication – Bulletin #1245, Athens, GA.

Ritz, C. and D. Cunningham, 2022. Best Management Practices for Storing and Applying Poultry Litter. University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Science Extension publication – Bulletin #1230, Athens, GA.

Vest, L. and W. Merka, 1994. Poultry Waste: Georgia’s 50 Million Dollar Forgotten Crop. I-206. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Science, Athens, GA.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2023. 2022 Poultry Production and Value Summary, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Washington, DC.